Research shows that schools with honor codes (especially those that are long-standing) report less incidents of cheating than those without them. But what if companies had honor codes? Would they reduce unethical behavior in the workplace?

First, let’s go back to schools to understand why some institute codes in the first place. If you are a business student, know this: MBA students are more likely to engage in cheating than any other type of masters student in the United States and Canada. In 2006, Donald McCabe, Linda Trevino, and Ken Butterfield published a study that showed that 56% of business graduate students had cheated at least once in an academic year – almost 10% more than other graduate students. Yikes.

As we mentioned in a previous post on cheating, in our research at Hult Labs we’ve talked to business leaders on almost ever single continent and, despite the various industries and functions they represent, the majority agreed on one thing: ethics are supremely important. Leaders expect that the business graduates they hire are going to have a finely tuned moral compass. Many of them even said that integrity mattered more than the “hard” skills students strive to develop and hone in their programs.

So just why is cheating more widespread now, despite the fact that employers want to avoid those who engage in it? In an interview with Jeffrey Davis, in The Company Ethicist, McCabe said this: “Because students see no reason not to cheat. They see others cheating and know how important their GPA is and, as a result, they feel compelled to do the same. I’ve had many students say to me, ‘you get those other students to stop cheating, you don’t have to worry about me. I’ll stop immediately.’”

In a New York Times article from last fall, a couple of other experts weighed in. Jeffrey Roberts and David Wasieleski from Duquesne University said they believe the ubiquity of the Internet plays a big role, as does the increasing emphasis on teamwork at schools. In the article, Wasieleski said: “Students are surprisingly unclear about what constitutes plagiarism or cheating.”

Howard Gardner, of the Harvard School of Education, holds a view that is as much a commentary on society as it is on a cheating scandal: “We want to be famous and successful, we think our colleagues are cutting corners, we’ll be damned if we’ll lose out to them, and some day, when we’ve made it, we’ll be role models. But until then, give us a pass.”

But Laurie Hazard, director at Bryant University’s Academic Center for Excellence, believes that schools themselves don’t do enough to drive home the consequences of cheating. In the article, she said: “Institutions do a poor job of making those boundaries clear and consistent, of educating students about them, of enforcing them, and of giving teachers a clear process to follow through on them.”

The article also referenced a study the Josephson Institute of Ethics had conducted on cheating among high school students. While 60% admitted to having cheated recently, 80% rated their ethics as higher than average. Clearly, there’s a disconnect. President of the institute, Michael Josephson, said that schools infrequently “place any meaningful emphasis on integrity, academic or otherwise, and colleges are even more indifferent than high schools.”

If the waters are murky when it comes to what constitutes cheating, and few schools do anything to illuminate the matter for students (nor make them face the consequences) it’s easy to see why students may (knowingly or unknowingly) take an unethical path. But when it comes to MBA students, McCabe says there’s another dynamic at play. In his article “MBAs Cheat, But Why?” he writes, “I believe the biggest issue is the get-it-done, damn-the-torpedoes, succeed-at-all costs mentality that many business students bring to the game.”

He goes on to describe how the vicious cycle of moral compromising starts, and how it can impact those who fall into it: “Achievers are trained, from an early age, to go for the ‘A’ – often regardless of the means – and as motivated ‘students’ climb up the corporate ladder, they are often more influenced by rewards than by their values. Their ethics become even muddier. As these people get older, many become more acutely aware of the gap between their professional (competitive) and personal (moral) lives; they become more psychologically frayed. Life, at least for them, has become a series of compromises.”

But some business schools have been stepping up their game to get students to forcefully think about ethics, and why making the right choices matters. Unethical breaches in the corporate world have been raising a lot of questions about how schools are shaping the next generation of leaders. “There’s really a gap between what goes on in business and what goes on in business education,” said Judith Samuelson, executive director of Beyond Grey Pinstripes at the Aspen Institute in an interview with MBA Podcaster.

The organization tracks the coursework of business schools around the world to determine which schools are prioritizing curriculum changes to incorporate social, ethical and environmental issues into their programs. Stanford Business School had the top spot in 2012. [They’re] “creating both opportunities for students, as well as making sure there’s exposure to the critical questions in their curriculum,” said Samuelson.

Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business has required ethics courses, and also coordinates student discussions on a variety of ethical situations in the corporate world. Said Dean Paul Danos in the interview: “There’s no doubt that the whole concept of ethics and integrity among business people is a very important topic…it’s something we have to keep emphasizing because it’s one of the foundations of good management…[but] even a person with integrity, if they don’t see these problems in context, they may not recognize them.”

McCabe, however, thinks the onus is on students. “Students need to take ownership and solve the problem. I don’t think we can impose a solution. That’s why I’m a supporter of academic honor codes.” He highlights Washington and Lee University as a prime example. The school’s code has been embedded in the culture of the school since the mid-1840s, and is entirely student-run. Every two years it’s up for referendum (the idea being that the newest cohort of students must choose to keep the system going). McCabe said that the school’s code has also deeply influenced many of the school’s alumni in terms of how they assert ethics and integrity in their own companies, and in their own lives.

Instituting an honor code, however, is not an easy feat. Honor codes are more likely to succeed in smaller, more controlled settings. And, it takes time, dedication, and perseverance to implement one, which is why instituting one at the corporate level is particularly challenging. But McCabe thinks that a company that makes the commitment to do so can reap the benefits, especially in the long run, once the code is ingrained in the company culture. “Short-term I’m pessimistic simply because the problem’s so deep rooted it’s going to take time to solve it. But I remain optimistic that we can do something ultimately.”

If you would like to find out more about our business programs, download a brochure here.

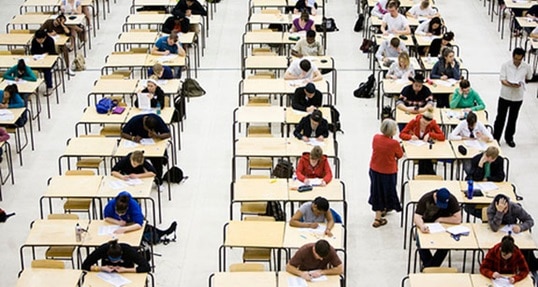

Photo courtesy of the University of Saskatchewan.

Hult offers a range of highly skills-focused and employability-driven business school programs including a range of MBA options and a comprehensive one year Masters in International Business. To find out more, take a look at our blog Introduce yourself and say #HiHult. Download a brochure or get in touch today to find out how Hult can help you to learn about the business world, the future, and yourself.