Extract from Critical Moments in Executive Coaching, 2021 by Erik de Haan

Rashomon describes a particular event as seen by different witnesses who contradict each other. They cannot all be right, and yet every version of the incident seems credible.

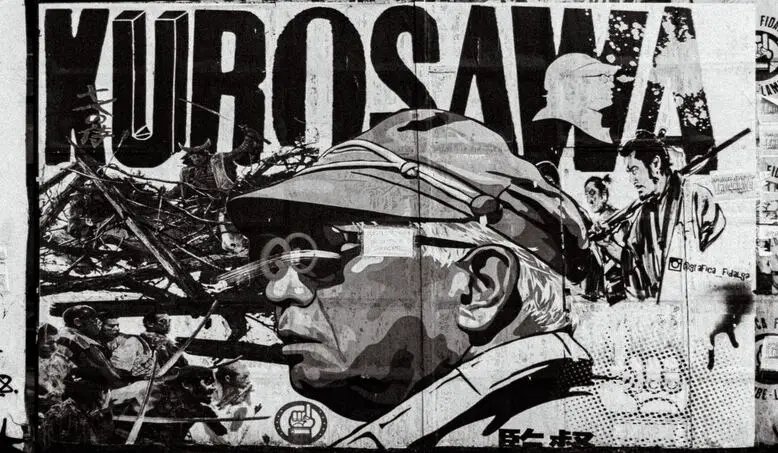

Rashomon is a 1950 feature film by Japanese director Akiri Kurosawa and one of the first Japanese films to enjoy immediate success in the West. Its theme is the impossibility of reconstructing the past from different testimonies. The film is still considered a masterpiece by many, for example, it is the favorite film of renowned Hollywood director Paul Verhoeven.

Rashomon describes a particular event, the attack and rape of a woman and the murder of her Samurai husband, as seen by different witnesses who contradict each other. They cannot all be right, and yet every version of the violent incident seems credible. The film’s existential plot has made Rashomon synonymous with the relativity of “the truth”. All of the witnesses’ stories seem perfectly logical and defensible, but there always turns out to be an underlying motive (lust, revenge, honor, greed, fear) for them to tell the story in this particular way and not another. The question remains: is there actually such a thing as ‘objective’ truth?

It is enlightening to view coaching conversations and relationships through the Rashomon lens:

This is how I experience our conversation. But how does the other person experience it? On the surface of the relationship, we both see the same things and hear the same words. Buy how do we understand those words, how do we interpret them for ourselves?

In this way, we can associate with our own experience of the coaching, and hidden aspects of the relationship (such as the underlying motives in the Rashomon story) also come into play. I often notice a relationship that at first glance seems straightforward and is spoken about as if it were straightforward, including, for example, defined contractual agreements, a clear purpose, and agreed goals, with one person in the role of coach and service provider and the other in the role of client, owner, and protagonist. Still, this very relationship can look very different from the inside. And also different for each party involved. A huge amount of work goes on below the surface. This is where we bring in our own anxieties and indirectly all of the relationships we have “practiced” with in the past.

Below the surface is the domain of transference and countertransference, where we as coachee and coach approach each other much more symmetrically, as two independent human beings each with our own needs and vulnerabilities. Here, very different stories are told. Here, basically, we continue to play out many earlier, significant relationships, especially if they are somehow unfinished or unsatisfactory. To navigate properly within any coaching relationship, we need to be open to this almost unknowable domain and remain genuinely curious about underlying motivations and anxieties. Otherwise, in the “above-ground”, explicit relationship, we will not achieve results that actually work.

We bring all sorts of unresolved patterns from previous relationships with us into our coaching sessions.

Let me dig around in my memory and find that undercurrent. Those taboos and buried tensions, the soft and dark underbelly of my coaching conversations, which I acutely felt at the time but rarely dared to address explicitly. Let me try to recall something of that more somatic experience, the rushes of adrenaline, sweat, and anxiety in my body, the simmering aggression, the attacks on the bearer of bad news, the mutual idealizations, the need for status and the stalking, the battle over who becomes the hunter and who the prey, heterosexual men deliberately choosing attractive female coaches or coachees, women feeling intimidated within the coaching relationship, etc.

Let me try to write a little Rashomon story based on my own coaching conversations. It is well established by now that we bring all sorts of unresolved patterns from previous relationships with us into our coaching sessions, hidden below the surface. Racker (1968) remains an authoritative text on transference and countertransference. He observes that there are basically only two underlying impulses in a relationship, which are also the hardest to overcome (in this case, to reflect on together rather than acting them out) during coaching conversations. These are the impulses of sex/love and power/violence. At the core, they may be parts of the same drive, because within coaching they are both clear attempts at subjection. In other words, under the surface, we can perceive “personal growth” on a very primitive and territorial level.

So…Sex

The worst thing that ever happened to me in coaching was in a first session, when I was so overwhelmed by someone’s physical attractiveness that my fountain pen began to leak incessantly and in minutes my hands were covered in black ink. A very Freudian slip that happened “of its own accord”. For the rest of the session, I tried to keep talking as normal, but I felt ashamed and was more concerned with my hands than with coaching. In the end, the coachee did not choose to continue in any case.

I am familiar too with the phenomenon of stalking and of wanting to get ever closer to the coach of one’s choice. In fact, I went out of my way to continue seeing my first therapist after successful treatment, for example, by joining a course he was teaching. And for years I have not been able to go on holiday without having to turn down special messages and requests to do a bit extra for someone, that is, with coachees signaling their secret wish that I would still be available on my holiday. And I often hear coaches in supervision talk about how they are “pursued” by coachees who keep signing up again for more sessions, but actually are mainly seeking closeness and intimacy; their benefit from those additional sessions in terms of coaching objectives usually turns out to be very limited.

There is a mutual idealization within the coaching relationship.

As a supervisor, I see many examples of sexual distraction from the task of coaching—colleagues who turn their coaches into life partners, coachees who choose a coach based on physical appeal, and coachees who start to flirt (or unexpectedly interpret warmth and attention as a “pass”), often precisely at those times when the coaching conversations are difficult and tough decisions need to be taken. See also Gray and Goregaokar (2010) as a study of sexual phenomena during coach-client matching.

And then there is a mutual idealization within the coaching relationship which I believe is sexual in nature, for example, the senior executive who has found a senior coach. The coach is proud of his coachee, and the executive is proud of his coach. Both have substantial reputations and each has now “landed” the other. I remember a coachee where this was very much the case. So much so that it took me perhaps eight to ten coaching sessions to say what I had seen in terms of a vulnerability in his leadership, namely that he had a strong need in all his relationships to keep things “nice”: warm, pleasant and agreeable, which made him sit on the fence when it came to conflict and challenge. Something I probably would have offered much earlier in the absence of those mutual expressions of estimation.

As is invariably the case (a “parallel process”, see Searles, 1955), the same thing happened in our relationship: I found our sessions pleasant and warm but did not realize that critical moments only occurred in the coachee’s stories, never between us. I had noticed this tendency on his part to soothe with warmth and courtesy but had never mentioned it, so much as I was basking in the (reflected) glow of this coachee. Until that is, he and I both came in for heavy criticism.

My coachee had lost the support of his supervisory board and had been fiercely criticized for his conflict avoidance and for failing to implement certain painful changes in the organization. This board meeting also raised the circumstance of the coaching, which had then been going on for almost a year. My coachee told me how I as his coach had been accused of only making things worse. He was very disappointed by this, not only in himself but also in the coaching. The meeting immediately led to a series of telephone conversations between us in which his threat to stop and find another coach hung constantly in the air. In the end, we both put on our hair shirts, and only then did we really get to work. Suddenly a much more challenging side emerged within myself, one which I knew from other coaching relationships, but had not thought necessary here because I conveniently believed my coachee was already so calm, distinguished, and accomplished.

And Power

Once I was contracted to gather impressions of the plant manager in a production company in preparation for our coaching sessions. There had been a lot of criticism in the interviews, especially that the manager did not intervene enough in cases of indiscipline or harassment and other goings-on between workers in the factory. I reported back as sensitively as I could and mentioned the essence of the feedback—with plusses and minuses.

Imagine my surprise when the plant manager first turned bright red in the face, then stood up, left the room, and headed straight for the executive wing of the company and the operations chief to complain about me. ‘I’ve been working here for twenty years and have never heard anything like this’, was his biggest gripe. He had not received any direct feedback on his performance for over 20 years. And after 20 years, he did not want to change that either, because he asked the director to dismiss his coach. In the end that did not happen: the plant manager and I worked together for many months at the request of the COO, although we never developed a truly warm relationship. It was more based on power and resentment.

Eventually, he did realize that he had let a lot of things slide and lacked authority on the shop floor. He agreed to step aside in favor of a successor who could act more firmly when things got out of hand between operators.

Often, organizational power permeates the coaching room.

Often, organizational power permeates the coaching room, with very different goals from those from within the coaching. I remember Matthew who headed the crucial “home country” of an investment bank but had been sidelined by the new CEO. Ahead of our meetings, I received various items of information about Matthew from the CEO and the HR director. Matthew turned out to be an enthusiastic coachee and worked quickly and energetically on his learning goals, some of which had been dictated by the CEO. However, as time went on, it became clear to me that the focus was not on the coaching, but on the complex negotiations to disentangle from the bank.

Matthew owned a large percentage of the bank’s shares and would benefit enormously from staying on for another year. Hence, at least in part, his enthusiasm for coaching and hence the continuing involvement of the HR director, who expressed dissatisfaction with the effects of the coaching. After working together for six months, Matthew and I felt we had achieved all the learning goals and Matthew proposed a three-way discussion with the CEO. The latter did not take up this invitation but was very keen to evaluate things for himself. He specified that I should send him my evaluation in writing.

On his part, Matthew was now working with a lawyer and also wanted a review meeting with me and a written report of that. So, at the end of the assignment, two different stories emerged about the coaching relationship: stories that might one day be contrasted in court, just like in the magnificent Rashomon movie.

But even on a much smaller scale, I often observe “power” and “competition” in coaching relationships. Being constantly contradicted by your partner in conversation, or infusing the conversation with tall tales to impress or win the other person over. Sometimes it is “airtime” as well, where my sense is that the coachee fills up the hour with a stream of words and associations, offering very little time for the coach to make a comment, possibly out of fear of what this comment might be.

These can be major obstacles to coaching unless you are able to raise the interaction itself and make it part of the learning process. Often it is the case that the kind of exercise of power you experience from your client as a coach will also be experienced in a similar form by others in the coachee’s organization.

And a special mention for money

Money is where sex and power come together, so money tends to signify much more than just spending ability, a healthy budget or even a sense of comfort. Only by understanding the hidden associations of money, and the extent of control and pleasure that money often represents to the unconscious, can we understand how someone could worry about another wage rise when they are already home and dry.

How often have I seen that “desire” for a promotion or better salary is the main reason to enter coaching, and then becomes the primary reason to stay away from the coaching goals, in other words, the desire itself becomes the main obstacle to really being coached. Blind fascination for what others might offer you can be very distracting from your own coaching agenda, even if that was where everything began for the collaboration.

Money tends to signify much more than just spending ability, a healthy budget or even a sense of comfort.

For coaches, it is all the more important to understand the attraction of sex, money, and power, and also to comprehend the deeper meaning of these sorts of “emoluments”, that is, the ability of these drives to fill apparent gaps or acquire alternative means of control. They can give you a “handle” on other people or on your work objectives which is ultimately corrupting as it goes beyond more open and rational ways of achieving the same.

If coaches cannot understand the motivations behind this blind (because largely unconscious) desire, we will achieve little in our conversations, and, if we cannot name these aspects somehow or try to interpret them in terms of transference and a deep deficiency in previous relationships, we will never get the real growth in the client’s circumstances. This demands a great deal of an executive coach, something that in my experience can only be acquired through intensive training and supervision, namely the art of understanding the whirlpool of desires and raw emotions while not allowing yourself to be carried away by it.

For a place to start, we often ask coaches on our training courses to think about a coachee they are currently working with. And then to imagine being marooned with this coachee on a deserted island. Visualizations like these, shifting the mind from brief, contained conversations to having to deal with each other full-time, often have a powerful effect. Try it with your own current coachee. Sniggers and laughter are never far away when we present this thought experiment to a group of coaches. Everyone recognizes the undercurrent when they transport themselves and their client to such an island, but only a few remain aware of it during their coaching conversations and are able to handle it in an ethical and reflective way.