The term “emerging markets” traditionally refers to countries or regions with inadequate economic welfare and structures. It’s also a label that is applied to economies that have in fact already “emerged.” It has become misleading.

Confused? Here’s an example. Until recently, The Economist viewed Singapore and Hong Kong as emerging economies. And the FTSE labels them as “advanced emerging markets.” But according to the World Bank, the purchasing-power-adjusted per capita GDPs of Singapore and Hong Kong in 2010 were USD $43,867 and USD $31,758, respectively. On this basis, Singapore exceeded Japan, Germany, France and the UK. And both economies ranked above Spain, Israel and Portugal. In contrast, numerous “advanced”, “emerged” and “developed” economies, such as Greece, Spain and Italy, are on the verge of economic contraction. They might even be described as “submerging” markets!

Moreover, the stigma once attached to the concept of “emerging markets” is no longer valid. Emerging countries tend to be seen as possessing small equity markets with levels of liquidity and price fluctuations typical of inefficient capital markets. In reality, however, equity markets in some emerging countries are sufficiently sizeable, with liquidity and volatility levels that match those of their more “advanced” counterparts. At the same time, the level of corporate governance in various emerging markets is moving close to, if not surpassing, levels seen in developed markets.1 As the distinction between emerging and developed markets blurs, the applicability of these descriptions becomes increasingly limited. It is no wonder then that The Economist (2008) called for the term “emerging markets” to be rendered obsolete.

The reality is that emerging markets are now the engines of the world economy, while developed economies are experiencing marginal growth, at best. Emerging countries have experienced above-average, if not substantial, GDP growth in recent years, although part of this has been the result of starting from a lower base. Clearly, a new term is needed to describe growing markets, hence Fast-Expanding Markets (FME). The fact that The Economist uses the term “emerging markets” while it simultaneously calls for a halt in the use of the term highlights the genuine need for new term to describe up-and-coming markets. Good thing we came along!

But perhaps the greatest problem with the term is that as long as markets are maintained as the critical unit of analysis, at the country level, it is easy to miss growth markets in countries with lackluster overall economic performance. If we only conduct analyses at the macroeconomic level, many growing business opportunities that have yet to contribute substantially to a country’s GDP will go unnoticed. It is exactly the identification of markets that are “off the radar” that create businesses advantages for companies.

For example, many researchers have viewed Japan as a languishing economy for the past two decades. Its traditional businesses are facing ever-mounting cutthroat competition from China and Korea, and it ranks low in competitiveness.2 From this perspective, it may be tempting to view Japan as a nation in continuous decline with few growth prospects, and to discount it as a potential source of new opportunities. However, this view reflects a focus on the country’s macroeconomic situations. If we look deep enough, pockets of exceptional growth can be observed. Whereas Japan’s consumer-electronic industry may appear to have passed its prime, its pop culture industry has been expanding in the global market.

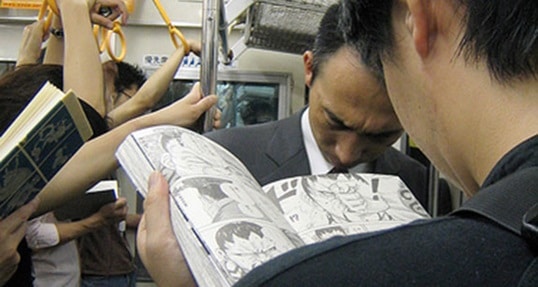

For instance, the popularity of Japanese comics, or manga, has been booming in the United States for the past decade, even though the genre is culturally distinct from mainstream American comics.3 The same is true of “cosplay,” a subculture originating from Japan in which people dress in costumes and take on the roles of various characters from animated series or computer games. In Japan alone the cosplay costume industry grew by 5% in 2009 to around USD $500M.4 Cosplay is becoming an important part of Japan’s pop culture exports. Indeed, a “World Cosplay Summit,” which was sponsored in part by Japan’s Trade Ministry and publicized by Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, has been held annually for nine years. This example illustrates that new opportunities exist at more granular levels, even in countries with stagnant or faltering economies.

We can look for a new configuration of how markets emerge by focusing on the pockets of growth that develop in a much more spontaneous manner than that which we’ve been trained to anticipate. Pockets are spontaneous in nature, rebellious in behavior, and expanding at a rate that would impress in terms of traditional indicators and analysis. Pockets of growth are cells of FEM in that they are embryonic transporters of new business opportunities that are often untapped and undetected.

Some may suggest that the term FEM is too broad to be useful. But we believe that it is exactly this characteristic that allows the term to encompass a vast variety of business opportunities and new sources of wealth, which can truly shape new seeds of prosperity. Only by broadening our horizons can we break away from the limitations imposed by such popular terms as “emerging”, “developing/developed” or even “frontier” markets.

Some may argue that FEM are nothing more than conjectures, as forecasting naturally entails disappointments. This may be true – admittedly, not every FEM will deliver promising results. However, analyses of the FEM phenomena should help us prepare for the future. In a sense, these markets are similar to a compass. While they may not provide enough information to pinpoint exactly what lies in the future, they can generate opportunities that honor real economy as the agency of development. It’s a brave new world where our global economy is concerned and it begs for a new term to help us evolve with it.

References:

1. Everest Capital (2009) “The End of Emerging Markets,” November, http://evcapan.com/documents/TheEndofEmergingMarkets.pdf, accessed on 7 November 2011.

2. According to the IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook (2011), Japan ranks twenty-sixth, putting it behind Qatar (8), Malaysia (16), China (19) and Korea (22), and just marginally above Thailand (27), the UAE (28), Chile (29) and India (32).

3. Matsui, Takashi (2009) “The Diffusion of Foreign Cultural Products: The Case Analysis of Japanese Comics (Manga) Market in the US“, Working Paper #37, Center for Arts and Cultural Policy Studies, Princeton University, Spring.

4. The Economist (2011) “Cosplay with me,” 10 August, http://www.economist.com/blogs/schumpeter/2011/08/japanese-pop-culture, accessed on 9 November 2011.

Terence Tse is a professor of managerial economics at Hult International Business School and Hult Labs Fellow.

Mark Esposito is a professor of global economics and corporate social responsibility at Hult International Business School and a Hult Labs Fellow.

Photo courtesy of Hiromy.